As someone past 70 and six years retired from my day job, I’ve enjoyed shifting gears, moving from wage slave to word slave. I’ve learned that becoming a writer, a novelist, later in life has some distinct advantages for me and, I hope, for my readers. I’ve also learned that it’s never too late to pursue your dreams.

One big change in my life post-retirement (we really need a better word to describe that time when a fulltime job is no longer a necessity) is that I spend more time reading fiction and, until the pandemic, attending readings by local and visiting authors, as well as visiting websites such as LitHub and reading magazines such as Poets & Writers. Although I don’t feel like a full-fledged member of the writing community, I like to think of myself as an affiliate. As an about-to-be-published author, I can participate in The Writing Life from a distinct perspective.

My first career was in public relations/public information at the University of Washington. Some people love what they do and love where they work. That isn’t how I’d describe my experience. Even though I did this for many years, I was never captivated by enthusiasm for my work. I was good at what I did, and I enjoyed the camaraderie of my coworkers. I relished the opportunity to stretch my mind in conversations with university researchers as they patiently explained their discoveries in fields ranging from astronomy to zoology, which I then translated into language that your average newspaper reader could understand. It was a kick.

But did I love it? Did I jump out of bed in the morning and jet off to work, eager to face the day? Not really. It was fun but not soul nourishing. So when a financial advisor told my wife and me that we had enough money to retire, I made immediate plans. I approached what they call in Spanish “la tercera edad,” which roughly means “the third phase” of life, with a mix of relief, curiosity and anxiety.

When I began thinking about the opportunities and challenges I wanted to take on, I thought about the novel I had penned in my 20s. I had no desire to reread it (and still haven’t), but I recalled the joy and compulsion that caused me to sit, night after night, filling blank pages with scenes from my imagination. But after decades of writing nothing over 1,000 words, did I have the attention span, let alone the wellspring of ideas, to stay with a project for more than a few days? Had my fiction muscles atrophied from years of disuse? I decided to find out.

But what would I write about? What was the story I wanted to tell?

At this point, I realized that waiting so long to resume writing fiction had advantages. The truth was, as a twentysomething I didn’t have a whole lot to say. I could put strings of words together in a clever manner, but to what end? Some 40 years later, thank God, I had matured to the point where I had fully-formed ideas and observations which I wanted to share with others.

In my spare moments at my day job that final year, I mused about what might be the essence of my first story. I would free-associate as I was eating lunch or heading to meetings, discarding most of the images that flashed across my brainscreen. It wasn’t long before I hit on what in journalism they call the “nut graf,” the essence of the plot in a few sentences. It was birthed out of two notions

The first was my decades of experience in a large bureaucracy. If you don’t find office work absurd you aren’t paying attention. Moreover, I think universities provide a particularly fertile ground for appreciating that absurdity. That’s because higher education is society’s temple of rational thought. What goes on in its laboratories, seminars and scholarly discussion is based on observations that are designed to be objective, critically reviewed and replicable. The scientific method is followed because, for its practitioners, it is the best path for finding truth – develop a method of investigation, let others critique what you’ve done and attempt to repeat it. What could be more rational?

What I found at a university was a gaping disparity between the rationality of the lab and what transpired in administrative offices. While scientific progress is based on vigorous debate, the bureaucracy often rewarded the powerful and those whose ideas were “The Flavor of the Month.” Once a policy position was adopted, it was treated as Holy Writ and was defended with a zeal that defied logical thought. In other words, universities operate like every other institution in society. Dilbert would be comfortable working at a university (as comfortable as he is anywhere). If you don’t find situations like this funny, then you may feel like crying. But reaction, my defense, had always been humor.

The second source of inspiration was a cartoon I had read in the New Yorker eons ago. I could tell you the details, but then I’d be spoiling the denouement of my novel. How these ideas fused in my brain, I have no idea. But when they did, I heard a bell ring. Not metaphorically, but literally I heard the sound of a bell in my head.

So I began with a premise and kind of an ending. But did I have the stamina to create a book? Just after retirement I began writing, with no outline, no plan. I knew where I wanted to begin. Then something unexpected happened: my characters began to live a life of their own, in my head and on the page. It was magic. I continued, day after day, following them and writing down what they did. I didn’t know where I was going exactly, but the process itself lifted my spirit and became addicting.

And about eight months later I had a novel, or at least a first draft. The path to publication has been circuitous and frustrating, but I think that’s what it is like for most novelists in the 21st century. Writing has become a key component of my “tercera edad,” in a way that I hoped for but never could have predicted.

More fun stuff about Ivy is a Weed and Robert Roseth is at https://robertroseth.com/

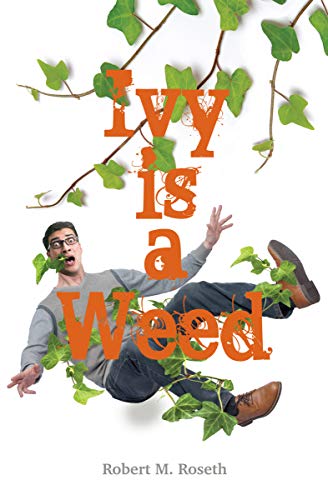

About Robert’s first book

Was Jeremy Ronson, a top-ranked university official, defenestrated (tossed out a window), or did he defenestrate himself? The police decide his death was accidental, but Mike Woodsen, the university’s PR director, is not convinced. He decides to investigate the death on his own. Woodsen interviews Ronson’s colleagues, an odd collection of administrators, nerds, suckups and misfits, and learns that Ronson had a justified reputation as a sonofabitch, earning many enemies in his chequered career. Meanwhile, Woodsen’s day job gives him a bird’s-eye view of campus life in the 21st century. He works inside a stifling but sometimes-comical university bureaucracy. that seems intent on its own self-destruction by advertising questionable claims—“Hey, we’re better than Harvard! Really we are!”–to enhance its reputation. Woodsen’s investigative skills lead him down several dead-end trails, but just when he is about to throw in his sweaty towel he comes across some clues that could be the skeleton key for unlocking the mystery. Has he solved a puzzle that police say doesn’t even exist? The conclusion he reaches is simultaneously absurd and totally logical. Ivy is a Weed is a murder mystery that will tickle your funnybone. It is in the tradition of Joshua Ferris’s Then We Came to the End and Jillian Medoff’s This Could Hurt. Fans of Dilbert will find the novel a logical extension of its humor, teleported to a university campus, while those watching reruns of The Office will detect a familiar aroma of absurdity and sarcasm.